National Advance Care Planning Week, from 20 – 26 March, is the perfect time for health and aged care staff to have important conversations with the people they support. It’s also a great time to support document completion and accessibility to enable a person’s will and preferences to be known, understood and respected.

The importance of advance care planning in enabling clear communication and helping to ensure that people receive their preferred type of care at the end of life has been emphasised by professional colleges and health and aged care accreditation standards.

Internationally, advance care planning has been defined as “a process that supports adults at any age or stage of health in understanding and sharing their personal values, life goals, and preferences regarding future medical care.”

This might include a range of actions. For example, a person might choose to:

- have discussions with family and friends about their personal values and what ‘quality of life’ means for them.

- identify a preferred substitute decision-maker and have discussions with them about the sorts of decisions they might need to make.

- consult with healthcare and/or legal professionals or spiritual advisors.

- make an advance care plan to provide guidance for family members or health and care providers about preferences for future care.

- document a legally authorised substitute decision-maker, and/or consent or refusal for specific medical treatments in a formal (legally binding) advance care directive*.

- review existing plans or documents, as their situation changes, and

- share their completed documents with those who may be involved in making decisions or providing care.

Enabling choice

Advance care planning is voluntary and grounded in the concepts of autonomy and informed consent, which are key principles in the Australian healthcare and aged care system.

With an expanding range of options for treatments and care, it is more important than ever that individuals are enabled to access realistic information about their situation and express what is most important to them. This can enable people to make decisions to accept or refuse different treatments or types and locations of care. Importantly, advance care planning is one way that the principles of autonomy and informed consent can be emphasised, even if a person is unable to make decisions or communicate their preferences, due to advanced illness.

Decision-making capacity

Decisions about future treatments or care options can be complicated, and completing a legally binding advance care directive requires that a person has sufficient decision-making capacity. There is no simple test for decision-making capacity, as it depends on the particular decision, at the particular time that the decision is being made. In general, a person is presumed to have decision-making capacity, unless there is evidence otherwise. If a person’s decision-making capacity is being assessed, the following abilities are relevant:

- The ability to understand the relevant aspects of the decision, and appreciate what this means for the individual, in their own situation.

- The ability to weigh up the information relevant to the decision, and

- The ability to communicate the decision in some way.

Decision-making capacity is best assessed through communication with a person about the decision and the different options available. Involving people who know the person well is very important, as this can help in interpreting a person’s communication, and understanding whether their preferences connect with longer-term views. In some cases, the involvement of professionals with specialised skills (e.g. in cognitive assessment) may be required. While we often talk about ‘making a plan now in case of a time in future when you cannot make decisions’, those who work in aged care settings understand the point of transition between having decision-making capacity and not having decision-making capacity is often not clear.

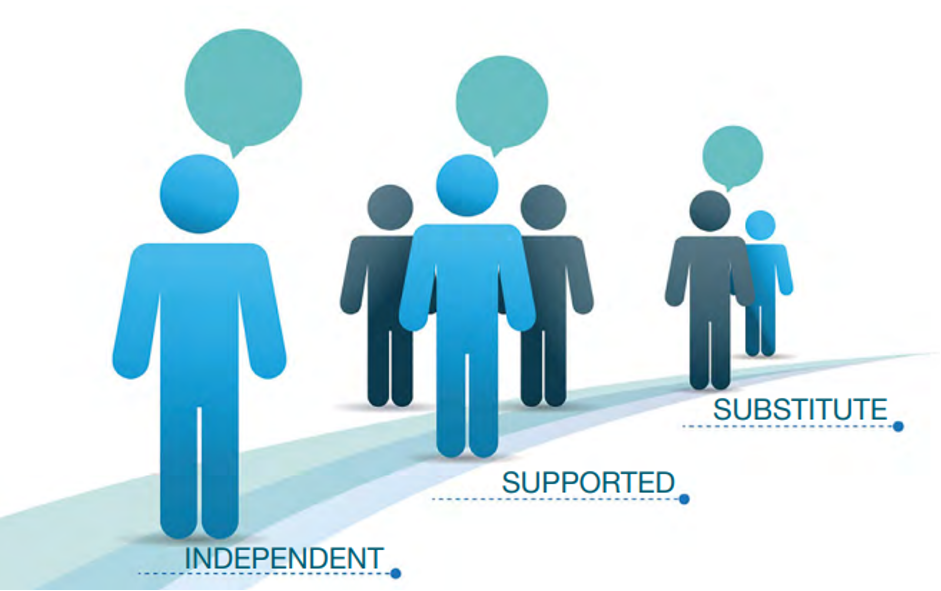

For people living with dementia or other neurological conditions, decision-making capacity can fluctuate from day-to-day, even while it may be generally declining. The presence of an infection, delirium or even general stress or poor sleep can impact on a person’s ability to make a certain decision. While there are inevitable ‘grey areas’ in practice, it is important to think about substitute decision-making as a last resort measure, and to consider how a person can be supported in decision-making. This can be seen along a spectrum, as shown in the figure below.

Figure 1: Spectrum of decision-making types

Importantly, regardless of whether a person is being supported to decide for themselves, or a substitute decision-maker is involved, the key principle is that the person’s will and preference is kept at the centre of the decision-making process.

This could be by helping the person to understand the decision, weigh up options and express their preferred option. Or if this is not possible, the substitute decision-maker should be focusing on using all the relevant information that they know about the person’s values, goals and preferences, and ensuring that these are being prioritised in the decision-making. A recent report for the Disability Royal Commission on supported decision-making explores this issue in greater detail.

The key practice points in this area would include:

- Consider accessibility of information about the decision. Adopt Universal Design principles, use pictures and text along with words, provide decision aids such as Talking Mats®, build off the person’s existing knowledge or skills and/or provide simple explanations that address the topic from a range of approaches.

- Knowing and understanding the person. Understanding a person’s background and life story can be very helpful. If providing care for someone who is unfamiliar, consider how the person’s existing support networks can be involved, to provide further information.

- Provide enabling decision-making contexts. Think about the optimal time of day, provide sufficient time for preparation, minimise distractions, and coordinate the involvement of other supporters if needed.

Further guidance and practice tips for supported decision-making relevant to aged care providers is provided by the Cognitive Decline Partnership Centre.

Life story work and advance care planning

A new project run by the University of New South Wales is exploring how combining life story work with advance care planning may be helpful in supporting older adults in decision-making. The project team is currently seeking expressions of interest from accredited home care package providers in the Sydney and Perth metropolitan regions. Organisations from outside this region may also express interest, subject to additional funding applications to support these partnerships. The research team can be contacted through the project website.

Access resources now

Organisations can embed quality improvement processes and ensure there are policies to support advance care planning upon admission to the service. This includes offering advance care planning to new residents or clients and asking if a person has a completed advance care directive outlining treatment decisions or appointing a substitute decision-maker. Make these documents available to your team and other organisations (e.g. hospitals, aged care providers and GPs) who are involved in the person’s care. Supporting staff with training to learn the principles of advance care planning and how to start conversations is essential.

Advance Care Planning Australia has developed an Advance Care Planning Improvement Toolkit for each state and territory to support each of these steps. Resources are available in 18 languages.

Find events and online webinars available Australia-wide during National Advance Care Planning Week at acpweek.org.au

Call the National Advance Care Planning Support Service on 1300 208 582 from 9am – 5pm (AEST/AEDT) Monday to Friday for further information and to request a free information pack. You can also refer a person with decision-making capacity, or their substitute decision-maker.

* While the names of the different legal documents that can be completed varies across Australian states and territories, all jurisdictions provide some way of formally documenting an authorised substitute decision-maker for health and lifestyle decisions. There are also formal documents for specifying consent or refusal for specific treatments, under specified conditions (either under statutory law or common law). Refer to advancecareplanning.org.au for guidance on the processes in your state or territory.

Dr Craig Sinclair, Senior Research Fellow, University of New South Wales, School of Psychology. Conjoint Senior Research Scientist, Neuroscience Research Australia